Many investors focus a lot on margins when looking for a good company to invest in. This makes sense logically. Selling a product for $200 that you paid $100 for is a lot better than selling the same product for $150. But margins, especially gross margins, can only tell you so much when it comes to the efficiency and profitability of a company.

For example, imagine two companies that sell the same products. They both purchase the product for $100 each. Company A is able to sell the product for $200 each, giving them a profit of $100 per product sold, which translates to a 50% gross margin. Company B sells the same product for $150 each, giving them a profit of $50 per product, at a 33% gross margin. Clearly Company A will be more profitable, right? Not necessarily. Imagine that Company B is able to sell two products in the same amount time it takes Company A to sell one. In that case, the gross profits of both companies will end up being the same.

Company A: 200 – 100 = $100 gross profit.

Company B: (150 x 2) – (100 x 2) = 300 – 200 = $100 gross profit.

It is clear then that gross margin, per say, doesn’t tell you if a company is profitable or not. The calculation has to include the turnover rate of the company. In other words, how fast can the company sell their products? Costco is an example of a company that has incredibly low gross margins, constantly at around 12-13%, but due to their high turnover and membership structure, they are still generating good cash flows.

There are a couple of different ways one could calculate the inventory turnover of a company, but the easiest and most accurate calculation is this:

You divide the costs of goods sold for the current year with the two-year average inventory. This tells you how many times the inventory of the company is replaced over the period.

Let’s take Costco as an example

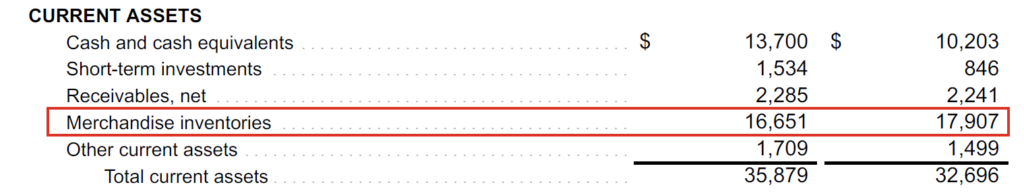

At the end of year 2022, Costco had roughly $17,9 billion of merchandise inventories, and at the end of 2023, they had $16,7 billion. The 2-year average is therefore (17,9 + 16,7) / 2 = $17,3 billion.

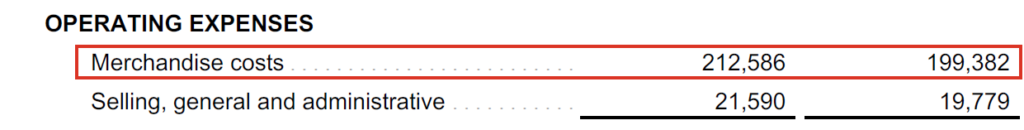

Looking at their income statement then, one can see that they had merchandise costs of roughly $213 billion for the year 2023.

Costco’s inventory turnover is therefore: 213/17,3 = 12,3. Having an inventory turnover of 12,3 means the company replaces their inventory once a month on average. Of course, the company has items that only stay on the shelves for a few days, while other items stay for months, but having a turnover of 12 times per year is relatively fast. As comparison, Best Buy had a turnover of roughly 7 times in the last year. Having said that, just like a high gross margin by itself doesn’t translate into profitability, a high turnover doesn’t translate into profitability on its own. Even a company that has higher than average gross margins and inventory turnover can turn out to be unprofitable if it is unable to overcome its operating expenses.

Let’s take another example

Company A purchases inventory for $100 million. The company then sell the products for $200 million, at a gross margin of 50%. The company has an inventory turnover of 10, meaning it replaces its inventory 10 times per year. The company will then generate a gross profit of $1 billion. Remember, they make $100 million in profit every time they turn their inventory, so $100 million x 10 = $1 billion.

Company B purchases inventory for $100 million, but sell their products at a lower markup. They sell their inventory for $150 million, at a gross margin of 33%. Due to pricing their products at a lower markup, Company B is able to sell more products, giving the company a turnover of 15 times per year. This will give the company a gross profit of $750 million (50 million of profit each turnover x 15 times = 750 million of gross profit).

In this example, Company B still generates less gross profit than Company A. The higher turnover wasn’t enough to fully compensate for the lower sales prices. But, remember that both companies have operating expenses that the gross profits need to overcome.

Imagine that Company A has operating expenses of 700 million, and company B, being much more cost-conscious, has operating expenses of only 400 million. Company A will then have an operating profit of 1000 – 700 = 300 million, while Company B has an operating profit of 750 – 400 = 350 million. So in the end, Company B turns out to generate more profit than Company A, even with inferior gross margins.

Conclusion

Even though a company has higher gross margin and higher gross profit than a competitor, it doesn’t necessarily say anything about their market position, or how attractive the company is as an investment. A company that is more cost-conscious and more efficient operationally may be able to generate higher operating profit and cash flows, and therefore be a more attractive investment. After all, it doesn’t matter how high your gross profits are if they don’t translate into real cash flows and earnings in the end. If your operating expenses eat up your gross profits, having high gross margins doesn’t do you any good.

Obviously, these examples might be oversimplified, and in reality, it will be hard to find competitors that differ that much in terms of operational efficiency, but my point is that you shouldn’t focus too much on margins. There are many ways a company can create value, and as an investor, you should focus on the free cash flow that the company generates through its operations. It doesn’t really matter if it’s by selling a few expensive items or a lot of cheap stuff. But you can’t get away from the fact that operational efficiency is very important. This is why many of history’s great value creators have been very cost-conscious.